Obscure Japanese Film #183 and #184

|

| Fubiki Koshiji |

|

| Machiko Kyo |

The

romantic comedy Ashi ni sawatta onna

began life as a magazine serial by the now-forgotten Nadematsu (or Nadeshiko? or Bumatsu?)

Sawada (male, 1871-1927) and was first filmed in 1926 (the year of publication)

by director Yutaka Abe. The story (in the two existing film versions anyway) tells of Saya, a pickpocket in Osaka who uses

her good looks to get close to men in order to steal their wallets. She’s just

served three months in prison and is on her way by train back to her home

village for the first time in many years. However, she’s not the usual criminal

type, and it emerges that her father was suspected of being a spy and committed

suicide, so she has been stealing in order to hold an expensive memorial

service for him and thereby get revenge on the villagers who ostracised him.

Also on the train are Saya’s grown-up but childlike younger brother, a bumbling

detective (who previously arrested Saya but is now on vacation), and a

pretentious, slightly-effeminate best-selling crime writer who learns about

Saya and wants to use her as the basis for his next novel.

|

| Tokihiko Okada, Yoko Umemura and Koji Shima |

In the 1926 film – which won the first ever Kinema Junpo Award for Best Japanese Film – the leading roles of the female pickpocket, the crime writer and the detective were played, respectively, by Yoko Umemura, Tokihiko Okada and future director Koji Shima. The former two died tragically young – Yoko Umemura (a favourite of director Kenji Mizoguchi) died at 40 following complications from appendicitis while working on Mizoguchi’s Danjuro Sandai (1944); Tokihiko Okada (the father of Mariko Okada) died at 30 from tuberculosis in 1934. Like the vast majority of Japanese silent films, that version is long lost and it’s unlikely that it still existed when Kon Ichikawa made the first remake for Toho in 1952, although he may well have seen it in his youth. Incidentally, according to Donald Richie in A Hundred Years of Japanese Film, rather than featuring a motley bunch of characters and having the bulk of the story set on a train, ‘The original Abe movie was about the upper-middle class in a hot spring resort.’ When he made the film, Abe had actually not long returned from a decade in America, during which time he had acted in a number of Hollywood films, so there’s little doubt that his work was heavily influenced by this experience.

|

| Ryo Ikebe |

Ichikawa

modelled his version on Hollywood’s screwball comedies of the 1930s, and top-billed

Ryo Ikebe as the detective appears to be attempting to emulate Cary Grant. It’s

certainly the most animated I’ve ever seen Ikebe on screen, but not his most

successful performance in my view. On the other hand, Fubuki Koshiji, who plays

Saya, is a natural comedienne and is in her element here. It’s a little

surprising to see So Yamamura mincing his way through his performance as the

presumably gay writer, but he stops short of full-on caricature, thankfully. One

nice touch is that his character’s niece is played by Mariko Okada, whose

father had played Yamamura’s role in the 1926 original.

|

| So Yamamura and Mariko Okada |

|

| Sadako Sawamura and Yunosuke Ito |

|

| Eiko Miyoshi |

A terrific supporting

cast also features Yunosuke ‘why the long face?’ Ito, Sadako Sawamura,

Sawamura’s brother Daisuke Kato and ex-husband Kamatari Fujiwara, and decrepit

old lady specialist Eiko Miyoshi. It’s a jolly ride which zips by in a

fast-paced and entertaining fashion, although some of the one-liners were no

doubt lost in the subtitles I auto-translated from Japanese.

|

| Kyo with Hajime Hana |

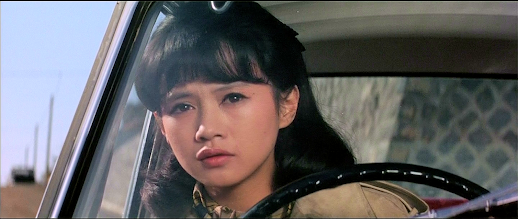

Daiei

produced a colour remake a mere eight years later, directed by Yasuzo Masumura.

Although Kon Ichikawa and his wife Natto Wada are again credited with the

screenplay, it appears to have been revised – whether by Ichikawa and Wada or

by Masumura I have no idea, but in neither version does the story make a great

deal of sense. In any case, the 1960 version seems more calculated as a vehicle

for a particular star – in this case, Machiko Kyo, who plays Saya in a more

blatantly sexy manner than Fubuki Koshiji, although she’s arguably less of a

natural for comedy. The detective is played as a much more slow-witted character

by the far less well-known Hajime Hana, but I found him more amusing than Ryo

Ikebe, while Eiji Funakoshi is slightly less effeminate as the writer than So

Yamamura had been.

|

| Jiro Tamiya and Eiji Funakoshi |

|

| Shiro Otsuji, Kyo and Haruko Sugimura |

Other notables in the cast include Haruko Sugimura in the

role formerly played by Sadako Sawamura, and Jiro Tamiya and Kyoko Enami making

early appearances in minor roles. Perhaps the most notable difference is that

Masumura puts far less emphasis on Saya’s motivation for being a thief and, in

fact, drops the memorial ceremony scene entirely – the cynical Masumura would

probably have considered this mere sentimentality. Personally, I wouldn’t

consider either version a must-see, but I slightly preferred Ichikawa’s on the

whole. He was obviously into it anyway, as he also directed a 45-minute TV

version in 1960 with Keiko Kishi as Saya, Frankie Sakai as the detective and

Tomo’o Nagai as the writer.

Note

on the title:

The original novel and

1926 film have a slightly different title from the remakes: Ashi ni sa hatta onna (足にさはった女), which could be translated as The Woman with a Scar on Her Leg. Although the remakes are usually

referred to in English as The Woman Who Touched Legs (or similar), the 1952 version at some point had the English title of Doubledyed

Detective, while the 1960 version

has also been known as A Lady Pickpocket

in English. Furthermore, it’s not entirely clear what is meant by the Japanese

title. Ashi can mean leg, legs, foot

or feet and, as there are no articles or possessive pronouns in Japanese, it’s

anyone’s guess whether it should be ‘her leg/foot’, ‘the leg/foot’, ‘a leg/foot’,

‘his leg/foot’, ‘their legs/feet’, etc. While it might be necessary to touch

somebody else’s leg when stealing a wallet from their trouser pocket, I think

the title is intended to refer to Saya’s legs – which she uses to attract men in

order to get close enough to pick their pockets – rather than those of her

victims, so The Woman Who Used Her Legs

would seem a better title.

Thanks to A.K.

1952 version DVD at Amazon Japan (no English subtitles)

1960 version DVD at Amazon Japan (no English subtitles)

English subtitles for 1960 version courtesy of Coralsundy