Obscure Japanese Film #115

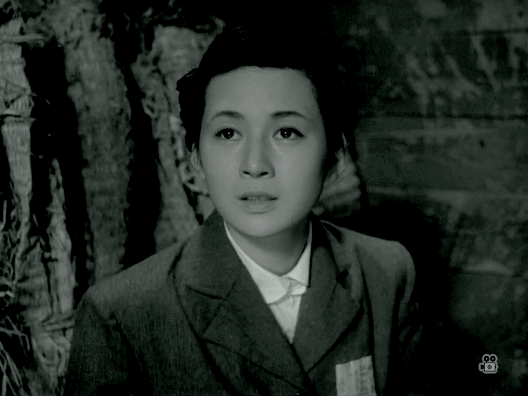

Yoko Tsukasa

1940. Baggy-suited university professor Wataru (Ryo Ikebe) falls for Kumiko (Yoko Tsukasa), the nurse looking after his ailing mother in the hospital. However, his best friend, Kojima (Yoshio Tsuchiya), is being sent off to war and wants Wataru to marry his sister, Reiko (Setsuko Wakayama). Wataru resists and, when Kumiko is reassigned to Hiroshima, he follows her but receives a telegram en route ordering him to report for military duty immediately. The two are separated and lose touch with each other amid the chaos of war.

|

| Ryo Ikebe |

Five years later, Kumiko has survived the A-bomb and is working for a man (Takashi Shimura) who runs a nursery school for orphans in Hiroshima. However, she has radiation burns on her body and the doctors believe there is a strong chance of her developing leukemia. For this reason, she believes that she is no longer fit for marriage and has changed her name in case Wataru tries to find her. In fact, Wataru has already tried to do so and concluded that she must be dead; he has married Reiko, but remains heartbroken. When circumstances lead him to suspect that Kumiko may still be alive, he makes every effort to track her down…

This wartime weepie was originally to star Ineko Arima, but she had to withdraw due to an eye problem and was replaced by Yoko Tsukasa, a Mainichi Broadcasting System employee who had never acted before but had just done her first modelling job and was spotted by director Seiji Maruyama on a magazine cover. Tsukasa proved that she was more than just a pretty face and became an instant star as a result.

|

| Takashi Shimura and Ryo Ikebe |

On the basis of this film, it should be unsurprising that director Seiji Maruyama went on to become best-known for his later war films as, while some scenes are indifferently shot, the movie suddenly comes alive during the impressive action scene in which Wataru and Kumiko have to flee their train along with hundreds of other passengers due to an aerial attack.

Given the storyline, this Toho picture can hardly fail to be moving, and indeed it is, but it also feels rather contrived at times, and the characters often fail to be as sympathetic as they’re presumably supposed to be. Wataru just seems to assume that his feelings are reciprocated by Kumiko and forces himself on her whether she likes it or not, while Kumiko appears to revel in playing the martyr. The film also tries to have its cake and eat it in that Kumiko’s only visible scar from the A-bomb (that we get to see anyway) is on one wrist, making it rather too easy for Wataru to dismiss it (compare this to the scene in A Night to Remember in which Jiro Tamiya is made to feel considerably more uncomfortable). One can’t help feeling that the bombing of Hiroshima in this film is little more than a convenient plot device.