Obscure Japanese Film #134

|

Rentaro Mikuni, Mie Kitahara and Jukichi Uno

|

Tamiko (Mie Kitahara)

is a young woman living at home with her stepmother, Nobuko (Yumeji Tsukioka),

and her bedridden brother, Junjiro (Nobuo Kaneko). Tamiko’s parents are both

deceased and she’s approaching the usual age for marriage, so candidates are

being discussed. Her father had wanted her to marry Komatsu (Jukichi Uno), an

easygoing nice guy who works in a munitions factory, but she’s not attracted to

him. Tamiko prefers the more aggressive and ambitious Ihara (Rentaro Mikuni), a

medical doctor who spends most of his time experimenting on animals when he’s

not womanising. However, she mistakenly believes that Nobuko wants him for

herself, and this becomes a major source of friction between the two women.

Meanwhile, Junjiro – who has never got over the fact that his wife left him –

is becoming increasingly obsessed with investing in stocks and shares…

|

Yumeji Tsukioka

|

This Nikkatsu

production was based on an untranslated 1955 novel of the same name by the left-wing writer Tatsuzo

Ishikawa (1905-85), whose work was also to provide the basis for several Satsuo

Yamamoto films, including The Human Wall

(1959). Ishikawa had actually been imprisoned by the Japanese authorities for a

few months in 1938 as a result of his novel Soldiers

Alive, which criticised the Japanese presence in China; he subsequently

avoided such topics until after the war. A

Hole of My Own Making was adapted for the screen by Yasutaro Yagi, who had

written a number of scripts for this film’s director, Tomu Uchida, back in the

1930s, before Uchida disappeared into Manchuria for a decade or so. The fact

that Uchida chose to work with these two writers and that the resulting film

shows so little regard for commercial considerations (with the possible exception

of its casting) leaves little doubt that it was a personal passion project and by

no means a routine studio assignment.

|

Nobuo Kaneko

|

Like Uchida’s previous

film, Twilight Saloon, it also seems

to be something of an allegory for post-war Japan, perhaps most obviously in

the character of Junjiro, a disillusioned and broken man pursuing financial

wealth for its own sake from his sickbed. However, despite the rich symbolism

that can be found throughout, I’ve seldom seen a film which leaves it so much up

to the audience to decide how to feel about the characters, especially in the

case of Tamiko and Nobuko. Who exactly are we supposed to be rooting for here? It’s

so unclear that it’s almost disorienting in comparison to the majority of

movies, and it’s difficult even to be certain about which character is referred

to in the title – a hole of whose own

making? Initially, I thought it must have been referring to Komatsu, who is

introduced at the beginning of the film sleeping in a drainage tunnel (?), but by the end I

thought it made more sense referring to Tamiko… Anyway, I personally enjoyed the film’s ambiguity, though I can imagine that some might feel exasperated and lose patience.

|

Mie Kitahara

|

Even more

unconventional is the harpsichord score by Yasushi Akutagawa (son of Rashomon writer Ryunosuke Akutagawa!),

which at times sounds like it's being played by a demented chimp. Weirdly, I kind of liked this too, and

you certainly can’t accuse anyone of going for the obvious here. Talking of

music, Nobuko and Ihara attend a koto

concert around half an hour in, and the blind musician we see performing is quite

something. He is Michio Miyagi (1894-1956), one of the all-time greats of

traditional Japanese music.*

|

Michio Miyagi

|

The actors are all well

cast and the performances solid all round. Mikuni dissects a live frog at one

point, and doesn’t appear to have faked it – unsurprising as he was known for

taking realism to extremes. The point was presumably to underline the character’s

lack of feeling, but I have to say that I thought it was unnecessary.

|

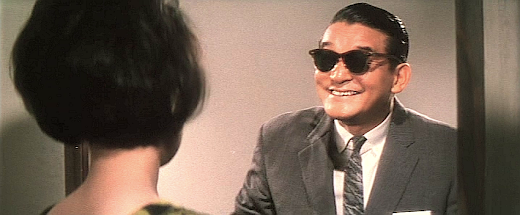

Mikuni with another unfortunate co-star

|

To return to the film’s

use of metaphors, a new sports centre is being built outside Tamiko’s family

home, and construction noises are audible in every daytime scene set in that

location – clearly a deliberate if unusual choice, and one that I think was intended

to suggest that the old way of life is coming to an end. As in the

recently-reviewed film A Rainbow at Every

Turn (1956), military jets fly over in several scenes, including right at the end,

implying an uncertain future not just for Tamiko and what’s left of her family,

but for the Japanese people as a whole. But Uchida never represents his

characters in this film as simple victims of change – many of them are

unlikeable and are pursuing selfish goals, and in various ways they bring their

misfortunes on themselves. Perhaps the title refers to more than one of the

characters after all, and of course it could be taken to refer to the Japanese nation as a whole, so A Hole of Our Own Making might have been a better fit.

*Despite his blindness, Miyagi also composed

the score for a 1935 version of Princess

Kaguya photographed by special effects whiz Eiji Tsuburaya. A shortened

version (33 minutes instead of the original 75) was rediscovered in the UK in 2015.

An excerpt can be viewed on YouTube here.

Thanks to A.K.

For more on A Hole of My Own Making, click here.