Obscure Japanese Film #187

|

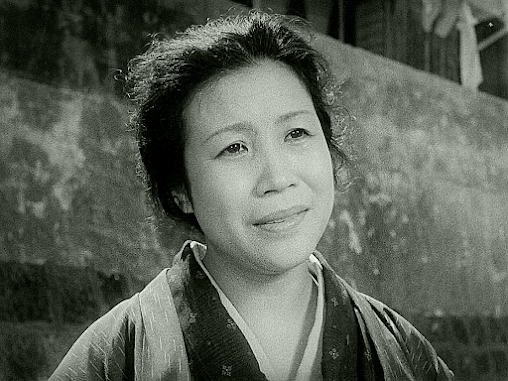

| Yuko Mochizuki |

Residing in a small seaside town in which fishing is the main industry, Okin (Yuko Mochizuki) is a single mother with a modest noodle restaurant where business is slow, so she hires former stripper Harumi (Mayumi Kurata) to serve the customers and keep them entertained, successfully increasing the number of male punters as a result.

However, Okin has an innocent teenage daughter, Oko (Yasuko Kawakami), who is about to graduate from high school and comes home one day to find her mother has gone to the shops and Harumi is upstairs having sex with a man. When Okin finds out, Harumi confesses that she had taken money from the man and offers to split it with her. Being a pragmatic woman who knows an opportunity when she sees one, Okin soon dismisses her qualms and it’s not long before she has half a dozen prostitutes living upstairs and noodles have become a mere afterthought.

Each of the women has their own sad story, including Mary (a young Kyoko ‘Woman in the Dunes’ Kishida), who has been separated from the child she had by an African-American G.I. Meanwhile, Oko attracts the attention of Kawai ((Eiji Funakoshi), a seemingly nice guy who gives her a lift on his bike one day only to take her into a secluded spot and rape her…

This Daiei production is a well-made and mostly well-acted film which deserves recognition for dealing frankly with some controversial matters. It’s surely no coincidence that, like Mizoguchi’s Street of Shame and Kawashima’s Suzaki Paradise: Red Light District, it appeared in 1956 when the question of prostitution was a hot topic in Japan (it was finally outlawed the following year, five years after the American occupation ended).

Women in the Attic suffers from a number of flaws – some plot threads are left frustratingly unresolved, while the transformations of both Okin from noodle woman to brothel-keeper and Kawai from nice guy to rapist are too abrupt to be fully convincing. There’s also, yet again, the misogynist cliché of a woman falling in love with her rapist – an unexpected element considering that the film was based on a novel published in 1950 by female author Sakae Tsuboi, who had also written Twenty-Four Eyes and provided the source story for Five Sisters (1954). However, it’s entirely possible that this was an invention of director Keigo Kimura and his co-adaptor, Toshiro Ide and, to be fair, this unfortunate aspect is somewhat balanced out by a scene in which Harumi confronts Kawai and slaps him so hard she nearly takes his face off.

Another point that bothered me is the following: Okin’s motivation for her new business venture is supposedly to give Oko a better life by being able to pay for her to have classes in ikebana and dressmaking, and thereby find a good husband. Of course, it’s no surprise that Oko is the one she ends up hurting the most, but the explanation given for this is that Kawai won’t marry her because she’s the daughter of a madam, whereas it seems clear from what we’ve seen of him that this is just an excuse on his part and that he’s simply a louse who would never have married her anyway. But perhaps I’m nitpicking too much – these misgivings aside, this certainly remains an interesting film worth seeing, partly for its refusal to vilify Okin, opting instead to portray her as a well-meaning but unfortunate and rather foolish woman.

Yuko Mochizuki, the unlikely star of this film, may have lacked film star looks but was a consummate actress who won awards for her roles in Kinoshita’s A Japanese Tragedy (1953), Naruse’s Late Chrysanthemums (1954) and Imai’s The Rice People (1957). A socialist, she later became a politician and even directed three films (with running times of 40-50 minutes): Umi o wataru yujo (‘Friendship Across the Sea’, 1960) about children being repatriated to Korea; Onaji taiyo no shita de (‘Under the Same Sun’, 1962) which dealt with the discrimination suffered by mixed-race children; and Koko ni ikeru (‘Living Here’, 1962), a documentary commissioned by the All Japan Liberal Labour Union portraying the daily lives of labourers and their families (see https://www.repre.org/repre/vol44/topics/tatsumi/).

Thanks to A.K.

Amazon Japan (no English subtitles)

No comments:

Post a Comment