Obscure Japanese Film #3

A film from 1982 about

an old hunter trying to kill an especially large and vicious black bear sounds

likely to be another schlocky Jaws

rip-off in the manner of Grizzly

(1976). However, the story actually owes more to Moby-Dick in that Heizo, the hunter in question, was attacked by

the bear some years previously and left with a bad facial scar as a result. As

played by Ko Nishimura, he seems too level-headed to seek revenge on an animal

for this reason alone, but further motivation is provided as the film

progresses. One of the many surprising things about The Old Bear Hunter is that the thinness of the plot turns out to

be something of an asset, providing a decent enough excuse for a film which is

as much a fascinating portrait of the little-known matagi as it is an adventure movie.

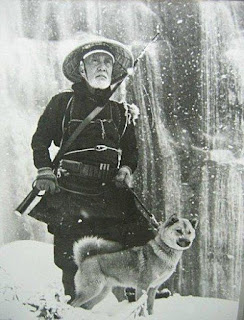

The matagi, traditional hunters often

accompanied by specially-trained Akita dogs, have been active in northern

Honshu for over 400 years hunting bear and other game. They consider these as gifts

from the mountain gods, and are careful not to waste any part of the animal or kill

more than they need.

The film opens with a

sequence on a snow-covered mountainside in which a bear is shot dead and the

hide removed. This appears to have been done for real, and The Old Bear Hunter is certainly a problematic film for animal

lovers. As in the case of the kangaroo hunt in the Australian film Wake in Fright, the filmmakers perhaps attempted to justify this scene by saying that the hunt was not staged

specifically for them, and they simply received permission to film a hunt that

was going to happen anyway. In any case, it certainly lends the picture a

remarkable degree of authenticity. Even more uncomfortable to watch are the

scenes of Heizo training his Akita – he slashes at it with a bear claw,

force-feeds it bear meat smeared with big dollops of bear fat, and even dons an

entire bear hide before attacking the hapless dog. Worse still, there is a

sequence featuring a matagi

dog-training competition in which a number of Akita are forced to attack a

chained bear. This scene goes on for some time and there is clearly no fakery

involved. However, if one can get past the brutality of these sequences, this

is a thoroughly absorbing and extremely well-made film.

This is also a film which

shows, rather than tells, and is therefore light on dialogue, something which

works very much in its favour. Director Toshio Goto makes full use of his

snow-laden, mountainous locations to often breathtaking effect, and the fact

that nothing appears to have been shot in a studio lends a sense of

documentary-like realism, while the esoteric details about bear bile, etc, suggest

that the ways of the matagi were

thoroughly researched in advance. Goto also skillfully manages to avoid lapsing

into melodrama and, when the climactic battle between old man and bear finally

arrives, it’s not only entirely convincing, but steers well clear of the sense

of triumphant revenge found in many ‘bad animal’ movies.

The Old Bear Hunter was Goto’s first film as director. Born in 1938, he

worked as an assistant director under Satsuo Yamamoto in the ‘70s. On IMDb, his

filmography has been mistakenly merged with another Toshio Goto who worked as

an editor on some of Kurosawa’s early films. However, the fact that he

subsequently made a Russian-Japanese co-production set in the wilderness of

Sibera entitled Pod Severnym

Siyaniyem / Under Aurora

immediately brings to mind Kurosawa’s 1975 film Dersu Uzala.

As Heizo, the diminutive Ko Nishimura is miscast in a role

that would have been better suited to a more physically powerful actor such as Toshiro

Mifune (perhaps Mifune turned it down). Considering this, he does very well in

the part and deserves respect for taking on what must have been a physically

arduous role at the age of 59. Nishimura made over 200 movies beginning in

1953, and will be a familiar face to most Japanese film fans, popping up as he

does in parts large and small in such classics as Sword of Doom and Red Beard.

If it were not for the scenes of animal cruelty, I would

wholeheartedly recommend this film to anyone.