Obscure Japanese Film #111

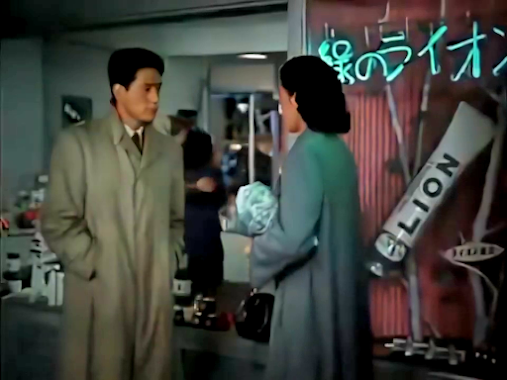

Yoshiko (Mako Midori) is a naïve country girl now living in Tokyo as a student. As she doesn’t believe in sex before marriage, her boyfriend gets frustrated and dumps her at a bowling alley. Seeing her left alone, Yakuza scumbag Yasui (Kei Sato) seizes the opportunity and slithers over to her. He takes her to a bar where he slips her a spiked drink, then takes her back to his apartment, rapes her and photographs her naked while she’s unconscious. When she awakes the next morning, he’s still asleep, so she leaves quietly, but within a few days he arrives at her apartment and shows her the photos, threatening blackmail. However, he offers to give her the negatives and all copies if she will sleep with pop idol Teruo Shima (Isao Kuraishi), explaining that Shima will pay him for providing a beautiful woman he can have no-strings sex with. Having no other choice, Yoshiko agrees but, when she goes to meet Shima, Yasui is hiding in the apartment filming them. Although Yasui keeps his promise and returns the photos and negatives to Yoshiko, she now has the film to worry about instead. Meanwhile, Yasui pays a visit to Shima to blackmail him, but Shima’s manager (Asao Uchida) hires unscrupulous lawyer Tokuda (Jiro Tamiya) to make the problem go away. Yasui finds that Tokuda is not easily intimidated – has he finally met his match?

This Daiei production was based on the novel Akutoku bengoshi (‘Unscrupulous Lawyer’) by Masaya Maruyama (1926-2004), who also provided the source material for director Yasuzo Masumura’s A Wife Confesses (1961). The fact that Maruyama was himself a lawyer is unsurprising considering that Tokuda’s legal shenanigans in the film seem unusually well thought-out, even if certain other aspects of the story do not entirely convince, such as Yoshiko’s rather sudden transition at the end. Some of the violence is not terribly convincing either, and we have scenes of slapping where there is clearly no contact but the patented sound of what sounds like a whiplash on sheet metal is dubbed on.

It’s impossible not to feel sympathy for Yoshiko, which begs the question of whether the police would really be as rough on a woman in such circumstances as they are here. Even Yoshiko’s mother seems to care little for her daughter’s welfare, and is far more concerned that Yoshiko has disgraced the family. It’s debatable to what extent these elements reflect real cultural differences or are clichés common to Japanese drama – certainly, similar scenes can be found in many other Japanese films of the era.

Although not one of Yasuzo Masumura’s most impressive films, The Great Villains has a compelling story and three strong lead performances, with Jiro Tamiya in another of the slippery manipulator roles he played so well and Kei Sato equally convincing as one of the most loathsome characters I’ve seen in a film for some time. Mako Midori, who resembles Mie Kitahara here, has probably the most difficult role and uses her eyes and body language most effectively in a part which gives her only limited opportunities for dialogue. She had just been fired from Toei at the time for complaining about the types of roles she was being obliged to play; she later went on to star in Masumura’s Blind Beast (1969).

The surprisingly stately classical music score by Tadashi Yamauchi suggests an attempt to lend the film both class and gravity, although Daiei’s dwindling budgets at the time are evident in the almost anonymous supporting cast and the fact that the work of Masumura’s regular cameraman Setsuo Kobayashi is less impressive than usual. Nevertheless, this is good second-tier Masumura worth seeking out for fans of the director, the three stars or Japanese crime dramas in general.

Note on the title: As there are no plurals in Japanese, it is debatable whether the title should be translated as The Great Villains or The Great Villain. Perhaps because the film is also known as The Evil Trio, whoever gave the film its English title has chosen the plural version. However, while the character of Yasui clearly qualifies as a villain and this term could also be applied to that of Tokuda, it certainly doesn’t fit Yoshiko unless intended ironically.